|

Bones of the Earth, Spirit of the Land

by Nicholas Capasso, Curator - DECORDOVA

Museum, Boston

Nick Capasso,

Ph.D., is Associate Curator at the DeCordova Museum and

Sculpture Park in Lincoln, Massachusetts. He is also an art historian,

critic, and lecturer in the fields of outdoor sculpture and public

art. In 1996, Capasso organized the DeCordova exhibition John

Van Alstine: Vessels and Voyages.

The Sculpture of John Van AlstineWhen asked to consider the intersection

of landscape and the visual arts, one immediately calls to mind

images of two-dimensional art, namely landscape painting and photography.

These two media - one ancient, and the other a product of the Industrial

Revolution - allow for both conjectural and relatively objective

pictures of our environs, seen always at some remove, as if through

a window. Or, in a more contemporary context one might consider

sculptural and architectural artworks placed within the landscape,

such as the site-specific earthworks or land art pioneered by post-Minimalist

artists Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Michael Heizer, and others

in the 1960s and 1970s. These works are not images, but objects

and places, inextricably tied to the land both physically and conceptually.

The sculpture of John Van Alstine occupies a unique territory, mediating

amongst image, object, and place. Van Alstine is a sculptor, first

and foremost, a maker of impermeable, obdurate, and often monumental

objects. These objects, however, also have an imagistic quality,

complete with the representational, associational, and metaphoric

qualities inherent to pictures. Yet at the same time they speak

strongly of place, in microcosmic and macrocosmic terms. Geology

and cosmology collide. Narratives about and within landscapes are

layered like sediment. Van Alstine mines the earth to excavate its

beauty, its terrors, and its potential for the expression of powerful

and subtle aspects of the human condition.

Even in Van Alstine's two-dimensional work - pastel drawings and

color photography - his concern for the landscape as stage and actor

is pre-eminent. This is not to imply that the artist's work is entirely

delimited by his perceptions of the land. He deals also with the

figure, the monument, abstraction, assemblage, storytelling (particularly

myth), cultural history, and natural history; but a sense of the

land, its gravity and embrace, its settings and stories, is the

ground upon which all else rests.

SCULPTURE

The hard root of the land is stone, and for Van Alstine, "stone

is everything," the physical and metaphysical basis of all

his work. None of his sculptures are without a stone, or the image

of a stone. Stone is the earth and the land, stone is terra firma.

Van Alstine uses stone as a place, a home, a figural presence, and

a magical transformational material. Stone marries nouns and verbs,

and dissolves the dualism of image and object.

Van Alstine grew up with stone, and lived close to the land, in

the Adirondack Mountains. He saw rocky promontories, glacial granite

boulders, stone walls, and split-stone fences in his boyhood travels

through upstate New York and northern New England. As an art student,

he saw stone as the foundation of the history of sculpture, and

began to believe passionately that "stone is sculpture."

Deeply impressed by the works of the ancients, he found compelling

parallels in Modernist sculpture. Van Alstine began his career as

a sculptor of stone by emulating the great abstract carvers of the

twentieth century: Constantin Brancusi, Hans Arp, and Henry Moore.

He chose white Vermont marble as his first medium for its softness,

purity, and malleability, and with it he carved sinuous, sensual,

biomorphic abstractions. Many of these works, like those of his

chosen predecessors, referenced the figure with their verticality

and suggestions of human corporeality, but many also were bound

up with the land. One of his earliest sculptures, Gaea (1973) is

an homage to Mother Earth, while the roughly parallel edges in works

like Vertical Series #3 (1974) were directly inspired by the tracks

of skis in virgin snow (Van Alstine had been a competitive skier

in his youth).

Soon, however, the young artist's interest drifted from the finely

wrought elegance of early Modernism to the rough-hewn rocks used

by sculptors like Isamu Noguchi. Van Alstine's intentions changed

and matured. He was no longer interested in carving stone to reveal

something else, but in allowing stone to retain its integrity, its

natural weight, density, and texture. By respecting the stone, and

allowing it to speak for itself on its own terms, Van Alstine was

able to summon forth a new and wide range of content. At the same

time, he shifted his process from the subtractive method of carving

to the additive method of collage in three dimensions. In 1975,

he embarked upon a series of Stone Assemblages. These were large-scale

outdoor agglomerations of rough-cut stones, straight from the quarry.

To these he sometimes added wood and steel elements in sprawling

compositions that dealt with the formal tensions among the three

disparate materials.

With the Stone Assemblages, Van Alstine laid out the beginnings

of the material, procedural, and compositional underpinnings of

all his later work.

In 1976, John Van Alstine moved to Laramie, Wyoming to accept a

teaching post at the local State University. While there, his love

of raw stone deepened, and his interest in landscape intensified.

In Wyoming he saw the land stripped bare, and saw clearly for the

first time the awesome power of nature as sculptor. The rocks of

his boyhood back east had been nestled in soil, swaddled by greenery,

and framed by the closely compacted rolling topography. Out West,

aridity, erosion, and the vast and stark lay of the land combined

to produce an unfamiliar sublimity. Mountains, buttes, stone arches,

glacial scars, exposed geologic layering, and colossal boulders

loomed about him and the real danger of rockslide and avalanche

was ever present. The bones of the earth protruded from its desiccated

flesh, and the landscape seemed a place fraught with potent and

perilous tensions.

In a new body of work, the Nature of Stone series, Van Alstine set

out to express his perceptions of this environment. He assembled

huge sculptures using nothing but giant slabs of Colorado flagstone

and forged steel rods. No pins or welds hold these materials together.

Their structural integrity depends upon actual physical forces held

in precise tensions and balances. In his Stone Piles, Arches, Torques,

and Props, the artist interlocked conflicting masses and weights

in arrested motions that strain with potential energy. They are

visually and physically precarious - their crushing capabilities

are palpable - and their scale and compositions echo the exposed

geology of the Western landscape. The Nature of Stone works explore

not only the bald facts of rock, but also deal with the tortuous

forces that underlie the landscape, the primeval tectonic writhing

of the Earth itself and its potential for extreme physical danger.

|

| Los Arcos, 1983 |

In the Nature of Stone, Van Alstine worked within the then-current

tenets of post-Minimalism, in which sculptors used minimal, predominantly

geometric forms and the direct properties of materials to elicit emotional

responses, often on a quite visceral level. In his next body of work,

Van Alstine set himself completely apart from his art historical roots

and his contemporaries. In 1980 he moved back to the East Coast to

teach at the University of Maryland. Shortly after his return, he

created a pivotal new sculpture, In the Clear (1983). This artwork

again brings stone and steel together, but now in harmony rather than

strident discord. The stone and steel elements embrace, and work together,

rather than seeming to try to pull each other to pieces. They dance,

rather than fight. Moreover, In the Clear refers not so much to the

structural properties of the landscape, but more to a sense of place.

This place is, to be sure, non-specific and highly abstracted, but

it seems a place upon the land rather than a force within the earth.

Van Alstine even went so far as to craft a vertical steel element

that suggests vegetation.

In subsequent sculptures, these direct landscape allusions proliferated

as Van Alstine continued to introduce aspects of imagery within his

dynamic formal and material assemblages.

In Drastic Measures (1984-87) and Luna (1985), the artist began experimenting

with applied color and quasi-representational shapes, to suggest plant

forms, and the moon and sky, respectively. In Los Arcos (1985), the

soaring steel member that unites its stone foundations makes conscious

reference to gigantic natural stone arches. And the compositions of

all of these sculptures suggest vignettes within the landscape, places

that can be imaginatively inhabited, and that are affectively distinct

from each other. In contrast to the Nature of Stone series, these

works are lighter, playfully evocative, and reflect the artist's fond

memories of Western places rather than his direct experience of the

powers of that land.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, Van Alstine arrived at the style and

themes for which he has become best known. He continues to juxtapose

stone and steel, but has added found objects and bronze castings of

stones and found objects to his set of assembled elements. The work

is ever more imagistic (especially given the presence of objects from

the real world) and increasingly narrative. The landscape vignettes

of the early 1980s seemed in part like empty stage sets waiting for

players and actions. Now, mythological and metaphorical tales are

told in sculptures wherein the distinctions between image/object/place,

and actor/action/stage, are marvelously blurred.

Two primary themes in this recent work involve tools and vessels,

and both are tied to Van Alstine's abiding concern with the land.

Struck by the collection of nineteenth-century tools at the Smithsonian

Institution's National Museum of American History, and following an

art- historical precedent established by David Smith and Jim Dine,

Van Alstine began to include actual utilitarian implements in his

sculptural compositions. He was most drawn to agricultural tools -

tools that help to work the land - and juxtaposed objects like rakes,

plow blades, saws, and anvils with his ever-present stones in celebration

of the joys and hardships of bending the land to one's will. Not surprisingly,

he was particularly interested in the sledge, an antiquated conveyance

on runners used for hauling stone over rough ground. In Van Alstine's

Sledges, massive rock slabs become carrier and cargo, both the landscape

and the laborious traversing of the landscape.

|

|

|

| Sledge 1992 |

Charon's Steel Styx Passage, 1996 |

Tether (Boy's Toys), 1995 |

The Sledges - stone boats - also relate to Van Alstine's simultaneous

involvement with the idea and image of vessels. The vessels - often

with nautical associations that turn his sculptures into abstracted

seascapes - involve metaphorical journeys across space, time, and

place. Marine scrap yards in Jersey City, New Jersey, where the artist

had relocated his studio, provided buoys, cleats, chains, oars, floats,

and boats, to juxtapose with slabs of stone. In works like Tiller

(1994), the stone flies aloft like a magical sail, and in the mythically

titled Atlas (High Roller) (1995), Labyrinth Trophy (1996), and Charon's

Steel Styx Passage (1996), the stones provide earthbound anchors for

sweeping, orbital narratives that link land, sea, and sky, as well

as ideas surrounding the boundaries between life and death. Other

vessel sculptures address a type of transportation that is as technological

as it is mythological. In Tether (Boys Toys) (1995), a huge airplane

fuel tank that resembles nothing more than a missile rises above a

puny earth, and in Sacandaga Totem (1997), a central stone pylon provides

the shaft to a rocket whose vertical aspiration is forever held in

check by its mass. Works like these indicate Van Alstine's concern

with the fate of the land, and of the earth, in the face of unchecked

science and industry. Taken as a whole, the recent sculptures that

involve tools, vessels, and voyages sum up and extend the formal and

conceptual issues explored in Van Alstine's earlier work. They also

establish places of contemplation not about landscape per se, but

about humanity's many physical, cultural, and spiritual relationships

with the land and our planetary home.

A great many of Van Alstine's recent sculptures are intended for outdoor

display, and the grounds that encompass his current studio in Wells,

New York (back in the Adirondacks) are filled with new work. In this

rural setting, framed by mountains, dense foliage, and a river, the

artist wrestles with issues of size, scale, placement, and sight lines

so that he fully understands each sculpture's potential for outdoor

display. His goal for all of his outdoor sculptures is to address

not only the landscape intrinsically, but extrinsically as well, in

direct dialogue with the natural features that surround them. Although

not entirely site-specific, Van Alstine's sculptures large scale outdoor

works do elicit meaning through their juxtapositions with existing

landscapes, and also transform places from the mundane to the magical.

PUBLIC ART

John Van Alstine's long involvement with placing sculpture in the

outdoors has led him on a number of occasions to accept commissions

for works of public art. These sculptures, chosen through competitions

and sited in public places, extend the artist's concerns with the

landscape by introducing site-specificity and conceptually linking

terrestrial place with cosmological space.

|

|

| Trough, 1982 |

Solstice Calendar, 1985-6 |

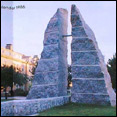

His first public sculpture was Trough (1980-82), commissioned by the

city of Billings, Montana to commemorate the 100th anniversary of

its founding. Trough consists of two mammoth leaning slabs of granite,

connected and supported by linear steel members, and could be considered

as the monumental culmination of the Nature of Stone series with its

references to geologic place, time and motion. But Trough exists as

something more. Its title and the relative positions of its stones

refer directly to the steep Yellowstone River valley into which Billings

is wedged.

The sculpture echoes the local rural sublimity of place in a downtown

urban space.

Van Alstine's next commission, Solstice Calendar (1985-1986), for

Austin College in Sherman, Texas introduced a new and enduring theme

to his public work: stone as a physical and conceptual mediator between

earth and the heavens. Solstice Calendar is a pair of colossal rough

Texas granite pylons that straddle a long horizontal stone member.

Every day at noon the sun passes between the pylons, and a steel bar

located high up between the pylons casts its shadow on the stone below.

This stone is marked to indicate the annual solstices and equinox.

This simple calendar was influenced by Van Alstine's study of ancient

archaeoastronomic architecture in the British Isles and Meso-America,

and by the work of contemporary land artists who also created

monumental yet basic solar calendars. Solstice Calendar not only locates

the Austin College campus in space and time, it also bridges academic

disciplines often deemed mutually exclusive by inhabiting a site directly

between the school's arts and sciences buildings.

|

| Artery Sunwork, 1993 |

In Sunwork (1989-1992), created for the Institute of Defense

Supercomputer Research Center in Bowie, Maryland, a soaring stainless

steel gnomon projects from a massive chunk of earthbound granite.

Here Van Alstine created another sculpture that acts as a scientific

instrument, but in keeping with its high-tech site, Sunwork is more

advanced and precise. It acts as a clock as well as a calendar.

In stone pavement around the sculpture, lines mark out the hours

of the day like a conventional sundial. Moreover, on a long horizontal

surface, an anelemma is inscribed. This diagram, shaped like an

elongated figure 8, shows the declination of the sun and equation

of time for each day of the year, corrected for the precise longitude

of the site. When the shadow of the tip of the gnomon strikes the

anelemma, it registers noon on any given day. Van Alstine's primitive

mathematical/cosmological computer helps locate this place in cultural

history, as well as within the landscape and the cosmos.

Sunwork was followed in 1993 by Artery Sunwork, in Bethesda, Maryland.

This sculpture combines the formal and conceptual concerns of its

two calendrical predecessors. Sited in a plaza along a heavily trafficked

urban avenue, Artery Sunwork consists again of an anchoring stone

that supports a soaring vertical element: an aspiring bronze arc

surmounted by a stainless steel gnomon. The shadow of the gnomon,

as it touches a precisely demarcated face of the bronze element,

indicates solstices and equinox. The sculpture thus carries a consciousness

of the relationships of place to earth to sky into the hustle and

bustle of downtown where such grounding truths are often ignored

or forgotten in a welter of streets, signs, lights, advertisements,

and architecture.

WORKS ON PAPER

Drawings

Throughout the history of art, sculptors have created drawings that

relate to their three-dimensional work, and John Van Alstine is

no exception. His drawings are large, richly colored pastels that

are neither working drawings for sculptures in process, nor two-dimensional

representations of finished works. They exist as separate and distinct

works of art, informed by and informing, but not necessarily tied

to, specific sculptures. Van Alstine uses drawing to further explore

his interest in the potential of imagery for expression. When images

occur in his sculptures - of tools, of vessels, of figures, of places

- the sheer physicality of objects imposes certain limits. But in

the illusionistic world of the two-dimensional, objects and images

are freed from the laws of nature. Without gravity, density, weight,

or friction, new and more dynamic juxtapositions and compositions

are possible, and narratives become more dramatic. Potential energy

explodes into kinetic energy. Objects teeter, swirl, loom, lurch,

and lean. The landscape comes alive, dances, runs, leaps, and turns

itself inside-out in paroxysms of joy and terror.

|

|

|

Sphere with Spikes |

Konos |

Greenhorn |

|

Hornhammer (green

handle) |

Photographs

Tellingly, between 1976 and 1980, when Van Alstine was experiencing

and expressing the powers within the Western landscape in sculpture,

he created a portfolio of photographs: the Easel Landscapes. These

18 x 24-inch color C-type prints are united by the presence in each

image of a flat and centered sculpted steel easel that frames particular

features within larger compositions. Made in and en route to and

from Wyoming, the Easel Landscapes provided the artist with a disciplined

process for literally focusing on the landscape, and they contain

some of his favorite landforms that reappear in his sculpture. As

works of art in their own right, however, they deal with multiple

issues germane to the intersections of photography and the landscape.

Their multiple nested frames (easel, photograph, paper mat, frame)

play tricks with perspective cues, and collapse or telescope perceived

distances, calling into question how the eye and mind perceptually

process the landscape via photography. The Easel Landscapes also

wryly comment on how the landscape is figuratively framed by photography,

experience, memory, art history, and popular culture.

|

|