|

Glenn

Harper, editor of Sculpture since April 1, 1996, was formerly

editor of Art Papers magazine, a regionally based, nationally distributed

contemporary arts magazine. Harper has written for Art Papers, Aperture,

Artforum, Public Art Review, On View, Afterimage, and many other

publications. He is the editor of Interventions and Provocations:

Conversations on Art, Culture, and Resistance, a collection of interviews

with contemporary artists published by the State University of New

York Press in 1998.

GH: Your work seems

to start with stone, even though you have most often used it in

conjunction with metal.

John Van Alstine:

Stone is central to my work, although I do most of the hands-on

work with the metal. My first stone works were carved, but it didn't

take long for the idea of smoothing out the stone, trying to make

it into something that it wasn't (the Arp or Brancusi influence)

gave way to artists like Noguchi and other influences such as Japanese

gardens where stone is accepted, even championed for what is. I

grew up in upstate New York and spent a lot of time in New England,

I vividly remember the rough split granite fence posts, sidewalks

and outcroppings of granite. I’m sure this early exposure

has had a impact on my interest in rough-hewn stone. But getting

back to your question, like many sculptors of my generation, particularly

ones that work with steel, I was/am influenced by David Smith, and

a kind of American “take charge” attitude toward the

material. So, yes I start with stone, but ultimately the work is

a confluence of different materials and approaches to them. The

duality of an eastern or oriental acceptance of stone and a 20th

century industrial American “can do” attitude toward

metal is at the core of my work and is, I believe, one of the important

things that distinguishes it.

|

|

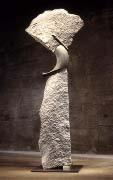

Chalice, 1995.

Aluminum, granite,

and steel

128 x 50 x 36 in. |

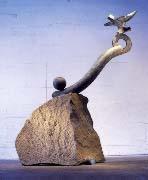

Juggler, 1994.

Green granite and bronze,

98 x 80 x 32 in. |

GH: What led you

to assemblage as a method?

JVA: Very early I

realized that I wanted to work larger, so I started using multiple

stones, and then introduced wood elements. I began using stone as

an additive element rather than carve it in the traditional subtractive

way. Some of pieces incorporated found curbstones that were pinned

together resulting in a gestural, 3-d calligraphic statement (another

oriental influence). The drilling channels in the rough stone gave

the work a "quarry graphic” adding a visual cadence and

reveled a history of how the material was extracted from the ground.

Also, because of their cylindrical nature, the channels suggested

a logical way to connected the stone via solid round bar which,

in the early sculpture appeared as sort of large staples.

Soon however I realized that I wasn't really using the full expressive

potential of the materials. If the work was about assemblage and

the nature of the materials, I felt I needed to create a situation

where each material revealed essential intrinsic characteristics.

In these early works the steel could have just as well been binder's

twine or rope for example, it wasn't essential that it be steel.

So, I eliminated the wood and started taking greater advantage of

the structural capabilities of the materials, creating systems of

interlocking steel bar to control and to hold the stone. Pieces

like Boundary 1976, developed where the granite is literally "bound"

by the steel in a way that the four stones rest on their edges with

an opening underneath. To assemble the work the stones are propped

up and the formed steel rod is wrapped around them, then the blocks

are kicked out and the whole piece settles into a bound position.

Because of the tremendous gravitational and real internal energy

involved, theses works were virtually “loaded" or "set"

much like a mousetrap. In fact, one thing that was exciting about

this series was I felt I was creating very “realistic”

sculpture precisely because of the real energy involved; much more

then say traditional sculpture or painting that rely on illusion.

Other pieces such as Crimp 1976 and Torque I 1976, developed where

the weight of the stone applied the energy to "crimp"

or 'torque" the bars together and actually provide the glue

that held the works together. Each element and its positioning was

a necessary one. The slightest change in the structure could be

enough for its collapse. I wanted the works to have a sense of arrested

motion and be kind of a static energy event. A large part of the

content of this series focuses on the idea of assemblage and I needed

the work to speak directly to that; it is assemblage about assemblage,

sculpture about sculpture.

GH: The relation of

your work to landscape seems to have a lot to do with the tension

of human effort in the landscape, rather than a "pure"

landscape, it's not Frederick Church, it's the farmer or laborer

at work in the landscape.

JVA: I am not interested

in landscape as an illusion. Because I'm a hands-on person for most

of my works, I relate to things at a scale which can be humanly

manipulated. I'm not personally interested in doing earthworks like

Micheal Heizer, with a giant bulldozer, but I do respond to the

idea of the farmer taking a plow cutting lines in the field. I relate

to what is done in or to the field, but I am even more interested

in the tools/ implements used and their functional and conception

relationship to the landscape.

GH: How did the landscape

in the West affect your materials and your ideas?

JVA: In the fall of

1976 I moved to Laramie to accept a teaching position at the University

of Wyoming. Up until then I had lived in the East were the landscape

is generally obscured by vegetation. The western landscape was stripped

bare, revealing the geology and conveying vast amounts of information

about its formation and history. Considering stone was my primary

material, all of this had a profound impact. There was a different

and empowering sense of scale, I was taken by the towering buttes

and unbelievable natural arches which ultimately let to a Totem

and Arch series that I still work on to this day. I was struck by

the overwhelming amount of sedimentary stone, created by millions

of years of layering. Sparked by Jackie Ferrara’s 1970’s

stacked plywood pieces and the way they were informed by the layers

in that material, I started building works that incorporated stacked

Colorado flagstone to echo or reiterate the nature of the material

and how it was came into existence. Coupling the "interlocking”

steel bar vocabulary that I had developed with massive stacked columns,

created structural systems that were not held together by welds,

but rather by the controlled and channeled gravitational energy

of the tremendous stone piles. In theory the higher the stack, the

greater the energy and the stronger the "glue" which held

them together. Some works in the series were left open on the top

suggesting the pile could continue indefinitely, recalling and paying

homage to Brancusi's Endless Column. They were titled Stone Pile

I, Stone Pile II and so on and like earlier works Crimp and Torque,

the title was both a noun and a verb indicating that the sculpture

was as much an action as a object. The more I worked on this series

the more I realized how much a fundamental human activity stacking

is, it was a common, universal form of “sculpture”.

We stack to store, to move, to count, to take inventory, to build

etc. I began to notice all kinds and ways, different shapes and

forms, with lumber, firewood, stone, hay, many types of architecture

etc., all of which further informed and influence new works in the

series.

|

|

Solstice Calendar, 1986

Granite and stainless steel,

20 x 29 x 20 ft. |

Delta, 1991.

Bronze and granite,

110 x 43 x 24 in. |

GH: Tripod with Umbilical

1982, is a work that marked a shift, a breakthrough indicated by

that line trailing off into the air.

JVA: I had moved to

back East to Washington, DC late in 1980 and for a while I continued

to work with sedimentary stones. But soon the influences of the

urban landscape and the feeling that I had exhausted the very tight

formulated interlocking no frills work, led me to consider other

options. The Tripod piece was almost like my flag going up to say,

"I've done this, and I'm beginning to break away". The

"umbilical" or squiggly steel bar was a sort of lifeline

back to where I had been and forward to something else. The next

important piece In the Clear 1982, combined this continuing need

to break away with a timely discovery of a supply of crushed I-beams,

pipes and tubes, as part of a subway construction yard just outside

the city. The piece incorporates a physical suggestion of vegetation

and in one way it is a landscape reference "in a clearing",

but at the same time it's about "breaking clear" from

that self-imposed restriction of only making work that was structurally

driven.

GH: The found objects

in the more recent works are ultimately as much landscape, urban

landscape, as the pieces that reflect the Western landscape.

JVA: In order to be

closer to New York I moved from DC to Jersey City in 1983. The industrial

and marine salvage landscapes there have had a major impact on my

work both as a source of found objects such as anchors, chain, buoys,

cleats; and as an place with unique and compelling characteristics.

Works like Link I and II, I feel are a sentinel pieces, and speak

directly to one of the core aspects of my work - the marriage of

very different materials - creating a meaningful amalgam from natural

and human made things. The large piece of chain at the center of

these works literally linking the elements is called a "pelican

clip," because of its shape and function of clipping large

pieces of chain together. The fact it is a connector, kind of "super

link", and because of its position in the work, intensifies

and underscores the central idea of union.

The calming characteristic of marine salvage yards, basically in

the center of busy urban environments has always surprised and attracted

me. Perhaps because it’s a transition zone from the intensity

of the city to the serenity of the sea, in any case, it has inspired

many works. Tether (Boys' Toys) 1996, for example, uses a 1500 pound

anchor to hold aloft a large piece of animated welded chain and

a wafting torpedo form. It generates a passive, almost weightless

feeling of being viewed from underwater. When I was working on it

I was reminded of the magic I felt as a kid when I first saw farmers’

mailboxes along a county road floating a top of welded chain. The

fact that the piece simultaneously conveys a sense of "folksy"

and “marine urban” attracted me. As the piece developed

further it began to suggest the model airplanes I built as a kid,

thus implying toys. The floating cigar/ missile/ penis form seemed

to demand that it reference “boys’ toys” which

added layers of symbolism and association. When completed I felt

it pitted playful innocence against sinister, rural against urban,

which created a very interesting tension.

I have several works that use large ocean buoys found in these yards,

in fact one is titled Buoy. It has occurred to me that the act of

making art is like dropping buoys as you bob along in your "stream"

of creativity, leaving floating reminders of where you've been.

Buoy 1995, attempts to formalize and convey this idea.

GH: So the found objects

link the stone actually drawn from the landscape with urban, rural,

and industrial environments. You mentioned tools, and a lot of the

found objects seem to have to do with working, with effort or fabrication.

JVA: As a sculptor

I've always been interested in tools, implements, and instruments.

I see them as extensions of the artists’ hand, important allies.

I am also drawn to their raw, efficient beauty of form dictated

by function. I am certainly not unique in using tools, David Smith,

Jim Dine, Picasso and many others have staked out some very impressive

territory. But I feel I have something to add to the mix based on

my unique experiences and perspective.

Growing up in New England for example, it is hard not to be impressed

by its beautiful stonewalls both in terms of the way they knit together

the landscape (they are the bones) and by the sheer pre-industrial

effort it took to form them. In Sledge 1992, I wanted to pay homage

to that effort and beauty by creating a piece based on the "stone

boats" or "sledges" that farmers used to use to drag

stones from their field to the edges, to build these walls. In the

piece the bed of the sled and its cargo were designed to be one

in the same, the single large flat piece of granite acts simultaneously

as both. There is something important about this union. Perhaps

it’s because it presents a “oneness” with the

material, tool, intent and final product.

Many of my works incorporate anvils either real or cast. Anvils

have the shape suggestive of a of a boat or vessel which implies

journey which interests me. But further, as a metal worker, it is

the place where I physically and conceptually forge things together,

there is an art spirit that comes off the anvil. It‘s almost

like an altar. I've titled many of these pieces Ara, which is Latin

for altar. Also, to me is the quintessential heavy object and to

get it up in the air creates a wonderful sense of tension.

I use references to tillers, both in the sense of the agricultural

implement and tiller as a navigational devise. The idea of an instrument

that aids one in carrying out decisions, to chart a course, is significant.

It can be seen as a metaphor for the very thing that distinguishes

us from other beings on the planet and provides a wonderful creative

vehicle. The scale or balance beam is a tool/ideal that provides

another vehicle, in part because much of my work is concerned with

physical balance. One piece in this series is Astraea's Beam 1991,

Astraea being the goddess of justice. Its un-natural positioning

addresses the question the equality in our contemporary judicial

system.

GH: There are other

seagoing references, especially vessels.

JVA: The ship or vessel

is a common and perhaps universal metaphor for passage used thought

out art and literature. Many of the found objects that I was attracted

to suggested boat forms and in an attempt to broaden my work, I

started to incorporate them. Actually the vessels in my work started

out first as containers influenced by my background as a potter.

I put myself through graduate school working as a production potter

and playing off the idea of a functional vessel is in my vocabulary.

The Chalice series, for example, starts with the suggestion of function,

but because of their scale (6-13 feet), the unusual combination

of materials and unnerving positioning of elements, they move beyond

function and transform all the elements including the open-ended

aluminum aeronautical fuselage into something akin to spirited “cups

of life”.

|

|

|

Tether (Boys Toys), 1995

Aluminum, granite,

and, steel,

16 x 14 x 10 ft |

Boys Toys II, 1996

Granite and bronze,

117 x 60 x 27 in. |

Buoy, 1995

Granite and bronze,

11 x 10 x 5 ft. |

GH: In this series

did you polish the aluminum to get the color?

JVA: Sort of. I took

a belt sander and worked through the applied paint reveling different

layers of color and in some places sanded down to the aluminum.

In a way, it's a lot like my drawings, where I'll add color, build

up layers of pastel, charcoal, and then go back with an eraser,

digging through to reveal some of what's underneath. For me drawing

is a release. It is similar to working with clay - putting material

on – taking it off, until an interesting balance is reached.

Like clay, the drawings respond to the touch, stone or steel demand

machine tools to be manipulated. I do drawings all the time, the

spontaneity and easy manipulation of the medium is a great counterpoint

to the often long, deliberate task of building a sculpture. Sometimes

the drawings are fantasy pieces used to develop ideas that may or

may not be impossible to translate to 3-d. Others are of finished

work, kind of a 2-d and often very colorful interpretation.

9A. Your color photographs

seem to deal directly with landscape, do they relate to your sculpture?

JVA: The photographic

Easel Landscape Series 1978-80, was a direct spin off from the sculpture.

In fact the 6’ steel easel central in all the photographs

was originally made for an indoor piece where I was exploring the

idea of framing. For fun I set it up outside and was amazed what

happened, there was an immediate connection to Magritte and his

paintings of the easel against a wall suggesting a window, the ones

where there is a painting of a painting; illusion of an illusion.

I felt there was potential for something in all of this and I began

taking it with me when I traveled. It actually became a great excuse

to get out into that wonderful landscape and feel like I was working!

I viewed the photographs as documents of sculptural installations

– the placement of the steel easel in specific landscapes.

They were about sentiment, perception, the convention of the frame

our inability to contain and compartmentalization that incredibly

expansive landscape. There were some of haystacks – Monet

Easel Landscapes; there were Abstract Easel Landscapes. I photographed

in places like the famous artists’ point in Yellowstone Park

conjuring the ghosts of Bierstadt and Moran. It was a very fun project

inspired and propelled by that fantastic landscape. Once I move

East, the urge to continue evaporated.

GH: How do you plan

the pieces? Do you select the materials first or match the materials

to an idea?

JVA: I seldom work

from a predetermined plan or drawing. I have a big reservoir of

found objects; stone, steel and other non-metallic objects. When

I travel I try to collect interesting things that I think someday,

somehow might inspire a piece. In the studio I do a lot of experimenting,

like an alchemist putting stuff together until something happens.

Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't, you keep at it until

you feel like you've got something. I like to use a fishing analogy;

you work hard to get a “keeper”, sometimes you have

to “throw it back”. The fun part is bringing desperate

elements together and never quite knowing where it's going to lead.

Usually the piece reveals itself as it's developing, in terms of

what the title might be or ultimately what it is.

GH: There is a figural

aspect to your work that is (except for the large public pieces)

it's at your scale, you are in the middle of it putting it together.

But there are also more explicit references to the figure.

JVA: For a long time

I really didn't want to acknowledge the figure, but I came to the

point where it was an conscious aspect of the work. Reconsidering

Sisyphus 1992, for example, is in a way a self portrait of my own

creative struggle. One of the ways to interpret the formal arrangement

of the stone and steel in this piece is as a figure frozen in the

act of prying or pushing a stone as in the myth of Sisyphus. In

a way that's what I do! I am out there literally pushing stone around

aiming for this very elusive place, and once there, I start over

again, with no real “end”. The title arises from Camus’

Myth of Sisyphus, where he “reconsiders” Sisyphus’

labors. For the artist the creative experience is not a goal, one

never just reaches the “top” and says “I’m

done”, but rather spins in a continual regenerative cycle

where the value and reward emerge from the process. It seemed like

a perfect analogy.

Some more recent pieces refer to movement of the figure, particularly

the Juggler and Pique `a Terre series. Pique `a terre is a term

from classical French ballet for a pose where one toe touches the

ground, the other foot is firmly planted, with a sweeping arm gesture.

Once you are aware of the title and you see the piece, the connection

is clear. I am in a sense choreographing these works, getting a

heavy weight off the ground and making it dance. Taking what is

often seen as a negative, the fact that stone is damn heavy and

a big hassle to move around, and turning it into a positive. It

is this transition that helps give theses pieces their magic.

GH: Do you select

stones rather than have them cut?

JVA: I have a flatbed

truck with a crane, and I go to the quarries or stone yards and

pick the pieces, bring them back and have them around in a kind

of “reservoir” to select from. Generally I look for

stones that have a fresh, clean, geometric character, they seem

to lend themselves best for combining with other materials. Granite

works well for my current work because it is very durable and can

stand up to the “abuse” I tend to put it through. I

also like its subtle, inert character. It does not call too much

attention to itself, is not a overly “pretty”. I also

am attracted to the subtle sparkle of the mica that is embedded

in it. Split granite elicits a similar ephemeral sparkle seen in

freshly fallen or drifted snow, yet it is such an obdurate material.

I like the contrast.

GH: For the large

public pieces, is there also a found-object quality in the stone.

Are you actually cutting a piece to match a maquette?

JVA: Landing large

commissions can be really tough for me. I present a scale model,

but there is no way that I want to go out and try to chip a large

stone into that exact shape. It would never have a sense of spontaneity

or freshness that I feel my work demands. So I’m always making

qualifications, saying "This is the spirit of the work, and

we will find a stone that will convey those same movements and characteristics,

but it's not going to be exactly the same – hopefully it will

be better!" The trick is to get the client or committee to

trust you so they are comfortable with this way of working, sometimes

that‘s hard.

GH: Your public works

have their own distinct imagery, they don't just use the smaller

works as a template. How did that develop?

JVA: I had a chance

to spend time in England and visited many standing stone sites.

It got me thinking much larger, thinking about placing stones in

a way that would track larger landscape forms or the movement of

the earth and ultimately create work with a more meaningful connection

to their site or setting. Trough 1982, my first large scale public

piece in Billings Montana, consists of two large slabs of granite

held in perpetual suspension by two interlocking linear steel elements.

In addition to being the climax of my early “tension”

pieces in terms of scale and raw power, the physically charged negative

space created between these very large “arrested” stones

was designed to echoed the main geological formation in the area,

an impressive trough cut through the high plains by the Yellowstone

River. This connection helps “seat” the work in its

locale and imbue it with even greater power.

Other public art pieces were in part influenced by sites out West,

like the Anasazi sun dagger, as well as Meso-American pyramids and

observatories. Solstice Calendar 1986, built for Austin College

in Sherman, Texas for instance, has two large, 22’ high columns

of stone connected near the top with a 4” diameter stainless

steel rod. The work is aligned north/south so that on the summer

solstice, light from the noon sun which is then at its highest,

passes light through the columns and creates a shadow which aligns

with the solstice bar on a third low horizontal stone element. Each

day that follows the noon sun is a bit lower, creating a shadow

a little further down the horizontal stone. It reaches the equinox

marker on or around March 20, continuing until it arrives at the

winter solstice bar where it reverses course and returns to complete

the cycle. The sense of time, space, place and the cyclical nature

of our existence evoked by the work transcends its physicality.

It is successful both because it directly addresses the ideas of

site-specific and placement and also provides multiple points of

access which allows a ”public art audience” to make

a meaningful connection.

GH: In a catalogue

for a 1998 exhibition at the Plattsburgh State University Art Museum,

you used the word "impure" to describe your materials,

in particular the found objects.

JVA: Found objects

are never “pure” in the sense that they are imbued or

tainted with layers of information, history, associations, symbolism

as a result of our individual experience with them in the “real”

world. Combining them together and with natural objects, like stones,

can result in a combustible mix that one can mine information and

elicit emotion, compassion, and reaction.

|

|

Tripod with Umbilical, 1982.

Yellow granite and steel,

72 x 80 x 92. |

Pique Terre VII, 1999.

Granite and painted steel,

6 x 8 x 4 ft. |

GH: More recently,

you've included another category of found objects, animal horns

and other organic forms. What led you to use those natural forms,?

JVA: The introduction

of organic, animal horns and other nautilus-like forms, is really

a spin-off from the arc that I've used a lot, a pure geometric shape

that is an ideal link between disparate materials. I've been looking

for ways to expand that idea. Currently I live in the Adirondack

Mountains where hunting is a big part of the history and culture.

You see a lot of mounted trophy heads – taxidermy is big -

in a way it is a local form of sculpture. I find many of the horns

very exciting from a purely formal aspect. Plus, like in Almathea

II 1998 and Hornhammer (Rouge) 1998, their use adds all kinds of

interesting symbolism and associations that can be woven into the

intent and content of the work. Once they are cast in bronze, you

can weld them and use them as you would any metal element. I’m

not sure where it all will lead, but it seems interesting at the

moment.

GH: Your use of color

has changed from the stone and steel works, to pieces with applied

color, to the combination of bronze and stone.

JVA: The stone in

the early stacked pieces is Colorado flagstone, it's kind of neutral

“pukey” pink in color. You'd stack it on the truck and

it would scrape and take its own marks of use creating an interesting

patina and revealing a sense its history. Because the stones were

all flat and rectilinear, the marks began to appear like writing

on a tablet, in a way describing what they were and where they had

been. That weird color was wonderful because I wanted the viewer

to focus on the stone’s volume, its weight, its history, its

geological layering, not how pretty it was. I have always been put

off by stone that seem too “pretty” or polished and

looks like plastic. They attract attention for the wrong reason

and seem too sweet. They hurt my “aesthetic” teeth.

In some later pieces I added color to the stone, thinning enamel

and letting it soak in. This was influenced partly by living in

the West where I came across stones that seemed unreal because of

their crazy shades of gold or yellow. By slightly tinting the stones

in the sculpture, I was able to tap into a similar sense of mystery,

getting to the point where most people didn't know if the color

was real or altered. This created an interesting tension.

When I started to use bronze one of the things I discovered was

the appealing range of color available though the patina process.

They were very subtle and natural, it struck a cord with my “ceramic

glaze” sensibility. As you can see I tend to cycle in and

out of different phases with color.

GH: How does that

sense of color relate to the more recent pieces with additive color?

JVA: The addition

of color on pieces like Drastic Measures 1984-7 or Luna 1985, and

others done around the same time, came as a spin-off of my work

with pastels drawings. At that time I was using mostly gray granite

and steel, which can be very monochromatic, and I got to a point

where I felt I needed more color excitement. This use of color differed

from the very early painted works that were more like stoneware

glazes, muted very earthy very low-key colors, influenced by my

work as a potter.

GH: In some of the

more recent pieces, like Column II 1999, there is a lot of color.

JVA: Yes, I guess

that's my recent reaction to late winter in the Adirondacks, it

seems mostly gray up there then. I started experimenting with color

again, with very flat enamels, first applying different and distinct

color on each of the geometric elements of a work, and staining

the stone. By the end of that series (there were five columns) I

began blending the colors, rubbing through them with solvents to

reveal some of the layers underneath. To mute things a bit I added

dark sprays, working the surface like my drawings. I guess working

through the cycle I ended up near, but not quite where I started.

This happens a lot with my work, it’s one way it grows. I

push out in a new direction, reaching a point of being uncomfortable

and then cycle back, hopefully not to the exact spot, stay there

for a while, then launch out again.

|

|

Offering (Running Column)

1999. Bronze and granite,

71 x 28 x 20 in. diameter |

Hornhammer-Rouge, 1998

Bronze and granite,

28 x 38 x 11 in. |

GH: When did you start

working in bronze?

JVA: Somewhere around

1988-89. There were a couple of reasons: maintenance of outdoor

works, and I wanted to re-use some of the particularly interesting

found objects in several different pieces. I work with a foundry

in Brooklyn that does sand casting, and that is great for me, because

in 99% of my pieces are unique. The fact that I am not usually interested

in editions makes sand casting efficient and reasonably economical.

I take parts that need cast to the foundry and retrieve their bronze

counterparts just the way they come out of the sand. I like the

rips, tears and textures that occur during the casting process.

I approach them like a new found objects, accepting and incorporating

their new information into the piece. Once back in my studio, the

bronze is fit with the stone and I do whatever welding or pinning

that is needed, then the patina is applied. Casting both expands

what I can do with the objects and introduces fresh important new

information to the mix.

GH: Your work has

a suggestive rather than a linear relationship with the mythologies

and the histories and landscapes that you refer to. Do you think

that comes from the additive way that you work?

JVA: I think so, as

I'm putting objects together I try to be very mindful as to their

individual associations, their past histories and ultimately what

they will communicate when combined. Sometimes when working a mythological

reference or interesting notion about the landscape will suggest

itself which provides a vehicle for comment or communication. I

guess the trick is to be ready or open to those suggestion when

they arise. Like most artists, I'm looking for common truths or

conditions that not only speak to me but make sense and connect

to a broader audience.

GH: All your work,

not just the large public art, has an epic quality - suggesting

the sweep of human history, a larger language or scope. Is that

an outgrowth of a conscious choice to look in the long view, the

large scale?

JVA: Yes, in my mind

significant sculpture or art strives to reveal universals, rather

than being navel-oriented. I'm interested in making statements or

raising questions that generate discussions on broad, universal

topics, uncovering truths that resonate and echo. I see my work,

when it is at its best, as a lens that can help provide focus to

a “big picture”.

|

Tiller, 1994

Granite and bronze,

96 x 93 x 64" |

|

|